Finally it’s the heat that gets me out of my sleeping bag. I don’t wanna do it; I don’t want to deal with the broken pavement that lies 50m away. But I have to. I’m packing up and eating the last cookies I had left over from yesterday, when I see what looks to be a motorbike going towards the border. I freeze instantly and focus on the oncoming vehicle. As it gets closer, there can be no doubt: it’s a touring motorbike carrying two people. I start running towards the road, the driver sees me and stops. It’s a couple from Spain riding back to Europe.

- Hi there! Do you have any uzbek money? I badly need to change 20$.

- I’m sorry we’re out. This is all we have left; says the man while handing me a 20.000 som bill. The equivalent of 2$.

- Thanks a lot. It’s better than nothing. Would you happen to have any water?

- Just a little bit. We can maybe fill up half of one of your bottles.

- I’ll take it. Thanks again. What can you tell me about the road? Does it get better?

- Yeah the road is gonna get better for you in about 20km. How is it going to Beyneu?

- You’re not gonna like it. But after Beyneu, it’s great.

We chat a bit more, I thank them again, we shake hands and go our separate ways. Well, this is just what I needed: a little water, a little money, and a big boost to the morale. I set out with renewed confidence. It’s 9.30 and it’s already pretty hot. There’s not much to see in the desert. The road is just a long, flat, straight line where you maybe spot a car every hour or so. There’s also the occasional wild camel. But that’s pretty much it. No turns, no trees, absolutely no changes in the landscape whatsoever.

And it’s hot. It’s too hot to hope riding 100km with half a bottle of water. I want to drink it all, but I only allow myself a sip every fifteen minutes or so. My mouth feels like paper. My mouth feels as dry as the desert. I watched every bottle lying on the side of the road, hoping to find a full one. Now more than ever, I regret the hours spent in my sleeping bag last night. Dumb mistakes are dumb. But mistakes you make knowing they’re nothing but dumb mistakes are even dumber. And very hard to justify. I soon realize it’s not gonna happen; I’m not gonna be able to reach the next shop with what I have left in my bottle. Something needs to happen. And it needs to happen fast.

That’s when I notice what seems to be a cargo truck straight ahead. As I get closer, I get confirmation it’s a big truck stopped on the road. I start sprinting frantically! I have to get to it before it leaves. It’s one of the longest minutes of my life. It’s my chance. If it goes away before I catch it, I may not get another.

Completely out of breath, I reach the truck and greet the drivers. Russian is the lingua franca in this part of the world and I quickly ask for voda, which, you guessed it, means water. One of the guys goes to a tank that is located underneath the truck somewhere and proceeds to fill up my bottles with lukewarm water. Meanwhile the other guy asks me “Otkuda?” (where are you from?) After answering “Francia”, I’m virtually out of russian vocabulary and the conversation comes to an end. I show them as much gratitude as I can (Spasiba bolchoï) and get back on my bike where I drink some of the water they just gave me. Drinking lukewarm water never feels good, no matter how badly dehydrated you are. But at least, I’m now in a decent enough shape to reach Jasliq.

On the map, the dot looks bigger than Karakalpakya. But when I get there, the village turns out to be pretty much the same size. It’s not big enough to have a bank or a hotel. It’s just big enough to have a shop with a fridge. That will do for now. Thanks to my spanish friends, I have enough money to buy either a little food and some water, or a bottle of Pepsi and some water. Thirst is far worse than hunger. Being hungry, I can deal with it. I can forget. Thirst is with you every second and never lets you the opportunity to think of something else. After so many hours spent dreaming of a cold drink, I know downing a bottle of cola is gonna feel much better than eating whatever. So I buy the pepsi. It’s almost frozen, which is perfect. I sit in front of the store slowly sipping the nectar. Kids look at me with their big eyes, wanting to talk to me but not knowing if it’s okay. I don’t mind being left alone. I stare at my phone wondering where I’m finally gonna be able to change money and get some food. The next dot on the map is pretty far and as far as I know it could be another small village deprived of any bank. There’s no way to know. Well, actually, there’s one. And it’s by getting there. So I get back on my bike and get going.

The rest of the day is just more of the same. This straight, lonely road across the desert, as far as the eye can see. There’s a good chance I did not enjoy myself. I honestly don’t remember. But I often think of this day in the desert. This particular day. And how quiet, big and peaceful this place was. I’m not sure I liked it when I was there. But in retrospect, I’m absolutely fascinated by how empty and remote this land is and I cherish the memory of how pure was the solitude I experienced.

I keep riding on the road whose surface has greatly improved. Sometimes the pavement completely disappears and I have to ride long stretches on gravel. But that’s okay, it’s still much better than the broken down concrete leading out of Beneyu. Around 20:30 I reach the next dot on the map. My odometer marks 238km, it’s dark and there’s nothing there.

There’s another dot what looks like 20km away. It’s a long shot since it looks as lonely and small as all the others I’ve seen before. If there’s nothing there, I’ll have no choice but to keep going all the way to Kungrad, approximately 70km away. I don’t know much russian, but I do know “grad” means city. A real one, with banks and hotels and maybe ATM’s. Of course, after 238km on an empty stomach, I’d rather ride 20 than 70km. But that’s not up to me. I keep pedalling while trying not to get my hopes up, as to avoid being disappointed.

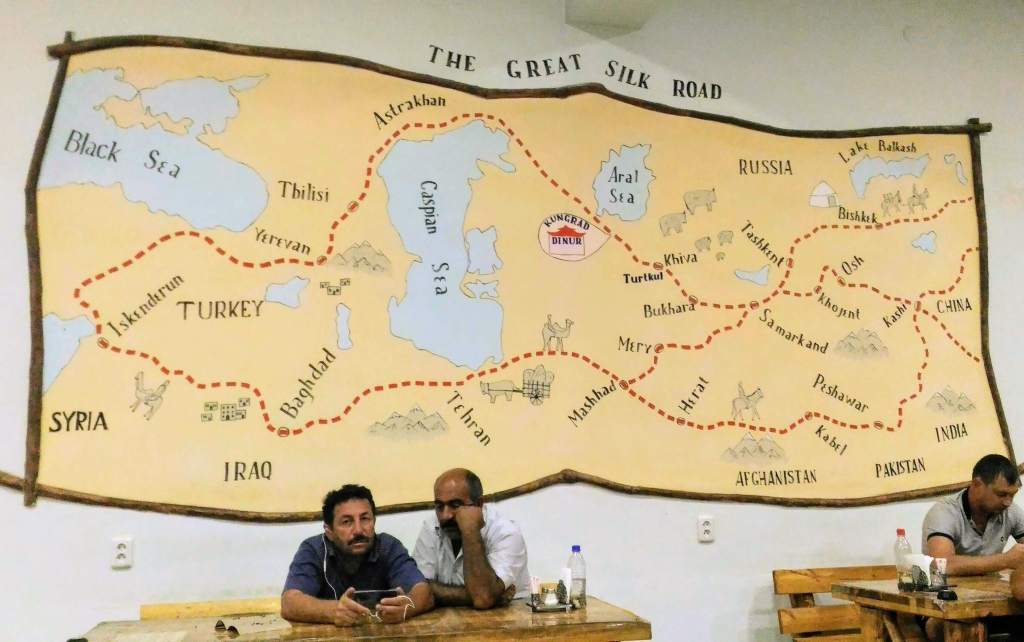

After a bit less than an hour, I reach the dot which was marked Dinur, and I see about two dozens of cargo trucks parked near what looks like a big restaurant. I can hardly believe it. I really expected another tiny village. Not a busy truck stop. I feel like I’ve really hit the jackpot!

But have I? Sure, they have food and lodging, but do they accept payment in US dollars? They cater to truckers most likely from any of the countries that are located between Turkey and China. So it would make sense to make business in dollars as well as uzbek som. The best way to know is to ask and I do just that. The waiter goes to her boss, she looks at me and nods her head: my money is good. It’s to describe how relieved and elated I am. Before making any other arrangements about spending the night, I sit down and order a plethora of food and drinks. After eating half of it, I’m stuffed. After spending so much time dreaming about this meal, it sure is disappointing. But you can’t let your stomach shrink with 36 hours of fasting and then fill it up like nothing happened.

I pay my bill with a crisp 20$ bill for both the food and the room, and then it’s on to a well deserved shower and a good night sleep on a cosy bed. 258km, 10 and a half hours of cycling, no food. It sounds a bit crazy, but when you don’t have any other choice, you just do it. This is the kind of stuff that can happen when you’re a bit too optimistic and you have an aversion to researching the places where you’re going. The funny thing is you’d think I have learned from such an experience. But the truth is, I haven’t and I made the same mistake again several times later in this trip. But it’s okay. Surprises should be part of any long bike tour. Who wants to know everything that’s gonna happen?